What does the data tell us about health inequality for Sickle Cell Disease in the UK? / The clinical and patient perspective.

There were over 150,000 avoidable patient deaths across the UK in 2020, a significant spike from previous years. Many of these patients came from an African or Caribbean background, not dissimilar to patients who live and struggle with sickle cell disease (SCD) each day in the UK. So, what do these findings tell us, and how does it all link to health inequalities?

Health Inequalities are avoidable, unfair, and systematic differences in health between different groups of people. They are rooted deep within our society, and they are widening – leading to disparate outcomes, varied access to services, and poor patient experiences of care. Much of this contributes to and results in earlier deaths, lost years of healthy life, and intergenerational effects from traumatic experiences, with significant economic costs for society. And yet, such health inequalities are often preventable.

As many already know, SCD is a hereditary blood disorder similar to diseases such as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TPP) and Fabry, not in terms of their pathophysiology, but in regards to their multi-organ effect, in that they are poorly understood, and in their lack of external, visible impacts. These are patients who may be going about their daily lives while experiencing intense periods of pain, but without anyone being aware that they have the disease. Indeed, patients from each of these conditions struggle with varying degrees of health inequality on top of the challenges of the disease itself and the impact on their day-to-day quality of life.

Building a true understanding of health inequalities, backed by real-world evidence

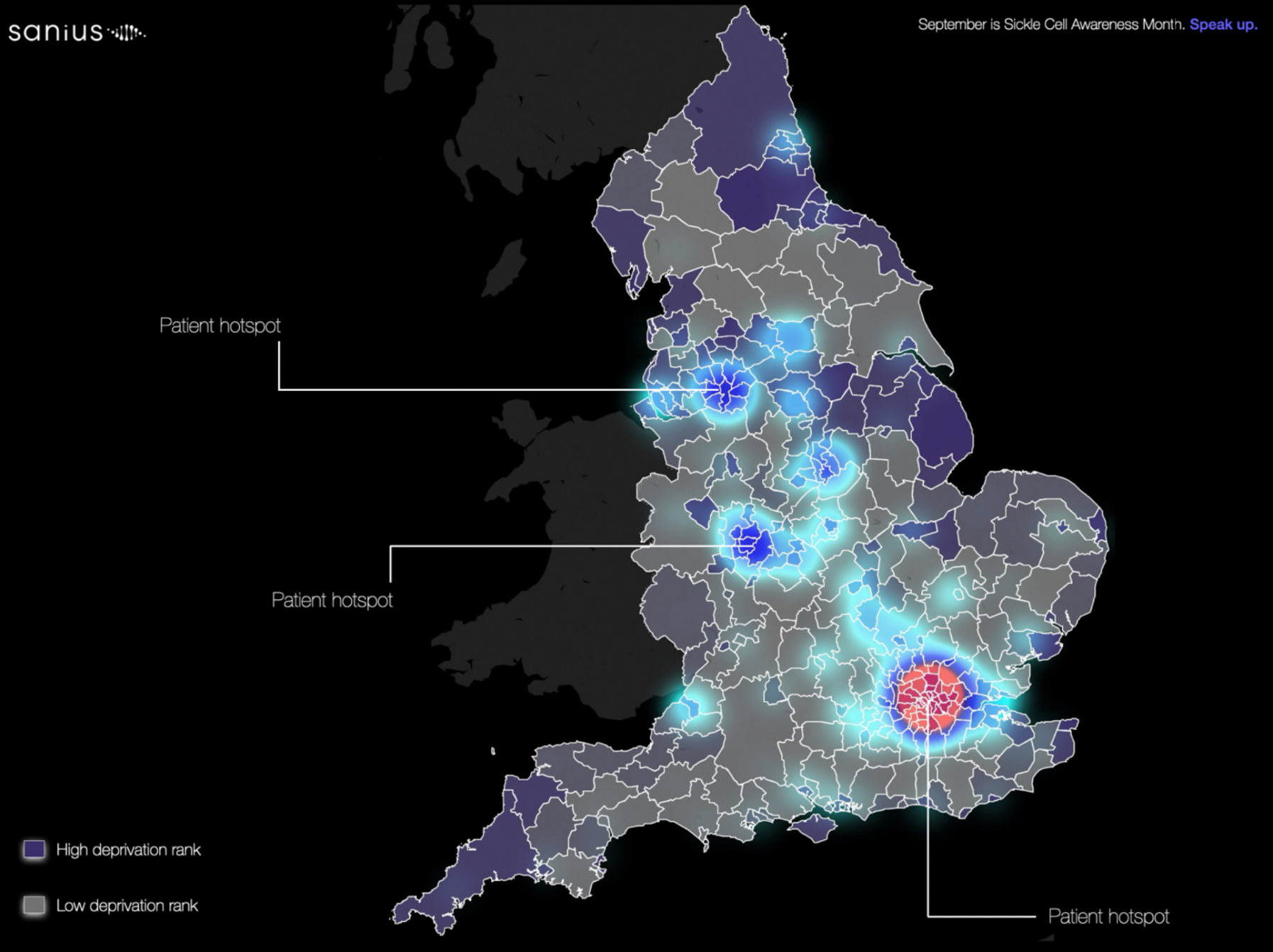

With geographical and deprivation data across the over 14,900 patients with SCD in the UK, we looked to understand what this means for patients living with the disease. Insights from the ONS highlight particular pockets of high deprivation within the country, indicated by the darker purple regions on the map below. Overlayed with patient volumes throughout each region – based upon their most commonly visited treatment centre – there is a clear disparity in the distribution of patients geographically and across deprivation zones, with smaller concentrations of patients in regions far removed from more specialised SCD treatment centres, indicating a real challenge for this patient group.

Critically, patient hotspots are seen across some of the most deprived areas of the country. Indeed, almost 50% of people living with SCD are most commonly treated in the 50 most deprived regions of the country. In contrast, across the 50 least deprived areas of the country, this is only 1%. These disparities in patient numbers across different levels of deprivation hallmark a potentially deeper issue and raise serious concerns for patients likely to be hardest hit by the upcoming difficulties of the winter months and cost of living crisis. As patients particularly impacted by the environment around them – temperature extremes running the risk of triggering severe pain episodes – something must be done to support these patients at their most vulnerable.

So how do we support the community and tackle health inequalities in sickle cell care together?

The Patient Voice

At the heart of progress is ensuring we listen to and act on the experiences of those living with the disease each day.

Esha, who lives in the North of England, shares that: “Access to out of hours specialist care remains a real issue for patients. A crisis does not care if happens during night or day, the pain will be there. Finally, many of us are on very strong opioids with dangerous side effects on our organs and mental health. These challenges are worsened by prejudice and assumptions that we are addicts.”

Oleander Agbetu, Community Development Officer at ‘Volunteer Centre Hackney’ worries that decisions made without considering the patient voice, like those around early transition out of paediatric care, will cause detrimental effects on young patients like her son Amiri.

“I’ve said it many times, to [Amiri’s] consultants and to doctors in general. But it doesn’t seem to make much difference, [although] this would not only benefit children with SCD, it would also benefit all children who are living with life-limiting conditions”

Understanding Complexity, Variation, and the Ever-Increasing Challenges Faced by Patients with SCD

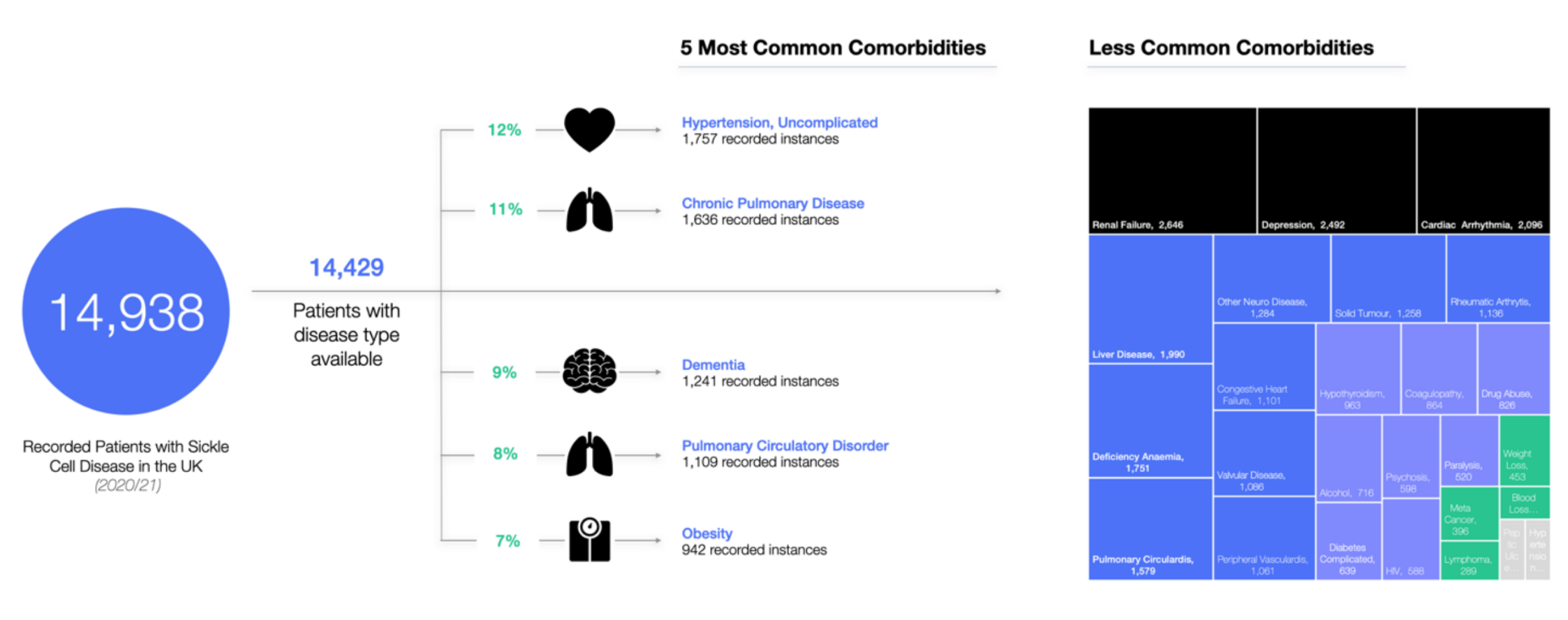

SCD frequently comes with a host of associated comorbidities, which create a significant impact upon patients’ physiological wellbeing, life expectancy, and quality of life. Considering patients with SCD facing an 8x greater chance of mortality than a non-affected individual of the same age, it is truly crucial to understand which comorbidities form the greatest burden across the country, and what the subsequent impact upon patient outcomes are. Early insights have highlighted challenges across the cardiopulmonary system, with hypertension and chronic pulmonary disease forming the two most coded primary diagnoses for patients with SCD in the UK.

These patients require integrated and personalised care in order to manage their conditions and prevent progressive, ongoing deterioration – the presence of multiple comorbidities highlighting the high complexity of patient needs in SCD. Despite this, patients face the same, historically, and unfortunately even to this day more limited access to care, with only a few new or existing therapies available to them.

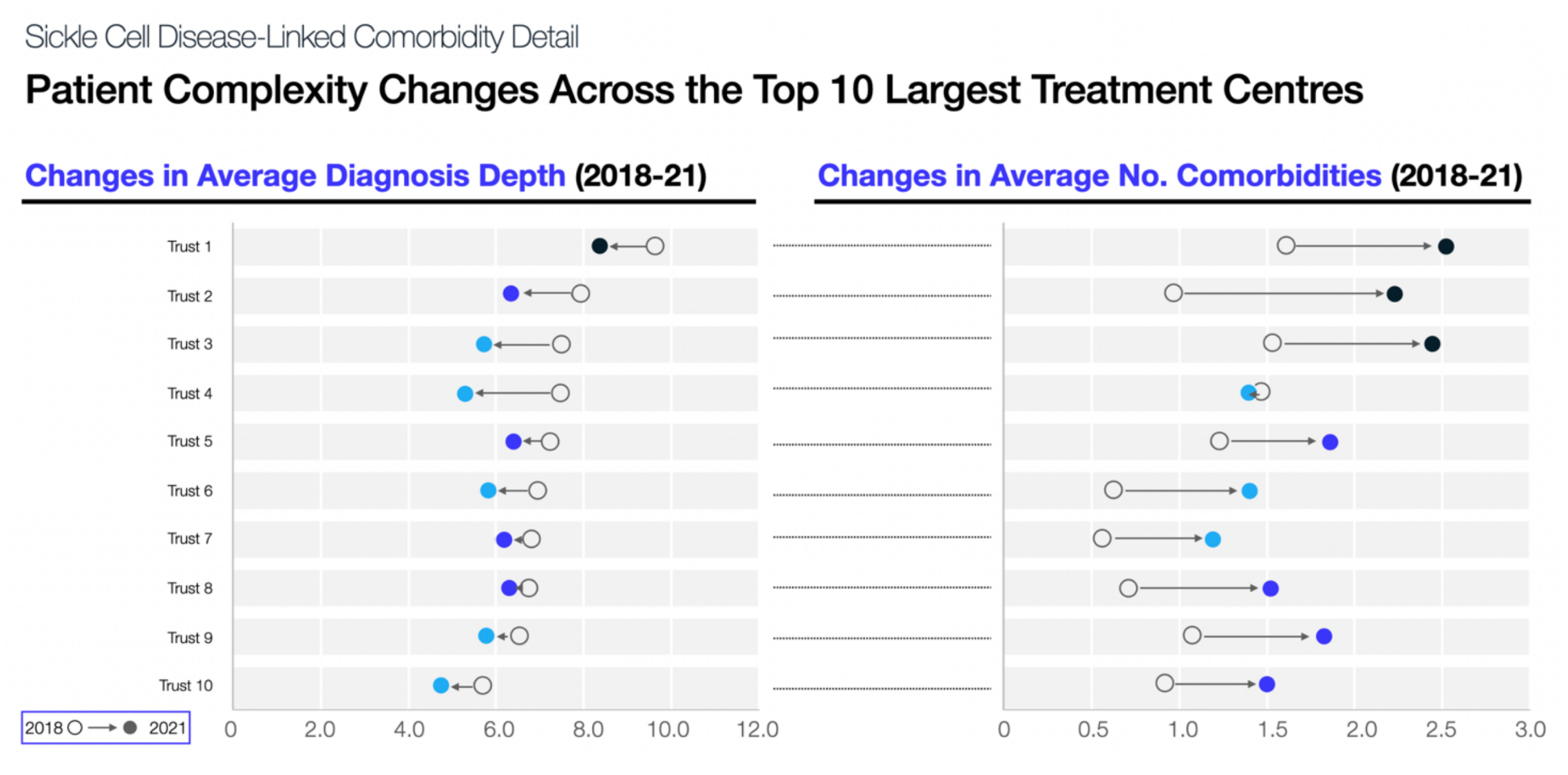

Even within this, clear variations between regions and treatment sites have been identified that pose additional challenges and considerations for patients and those responsible for their care. Indeed, while the average diagnosis depth of admitted patients has shown an overall decrease from 2018 to 2021, this has not been true of the comorbidities and disease complexity of each patient. At all but one of the 10 largest treatment centres for SCD, the average number of comorbidities reported for each patient has increased since 2018, at an average of 0.8, and at largest 1.2. With greater patient complexity therefore comes the need for improved pathways of care, to ensure disease management matches the needs of these patients.

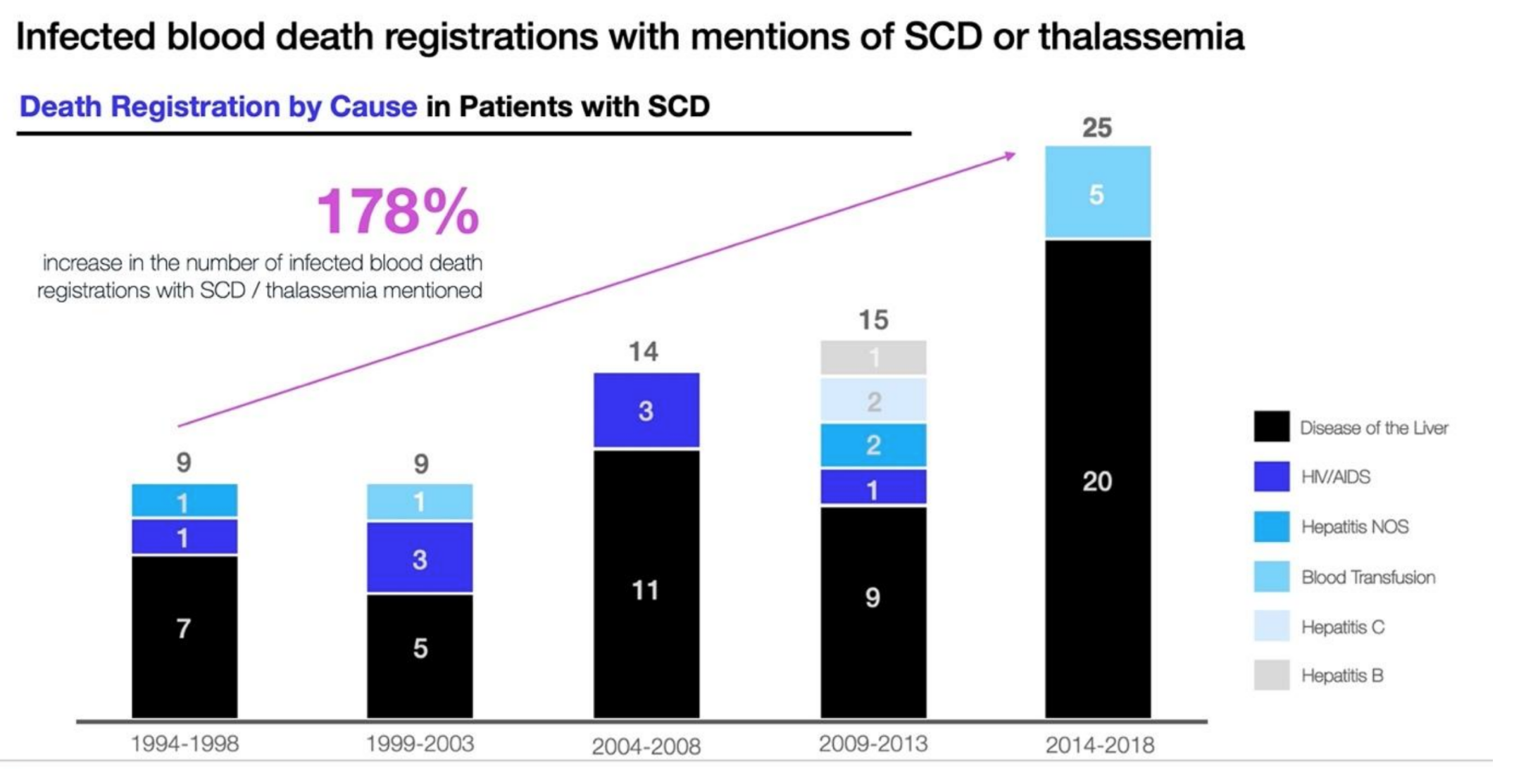

Exploration of some of the key areas of care for patients with more severe or chronic anaemia has seen particular focus on data potentially linked to blood transfusions – a vital component of the care pathway for many with SCD, but one that unfortunately sees ongoing difficulties in regards to access and prioritisation. Notably, as one of the few treatment options currently and historically available to patients with SCD or thalassemia, the extreme increasing numbers of infected blood related deaths over the years is truly a disturbing one.

In a landscape were reducing potentially avoidable mortality in patients is such a prominent national and global point of focus, these increasing mortality rates across all sources of infected blood deaths in SCD and thalassemia over recent years is one that highlights an urgent need for new ways to tackle the underlying causes – protecting this historically overlooked patient population from further, unnecessary harm.

Recent conversations with our clinical colleagues have made it all too clear how longstanding and devastating these kinds of health inequalities have been for patients over the years. Without recognition of the need for specialist care, patients have often been treated across various specialties that are not necessarily equipped to support patients with SCD. A critical component of this has been a lack of visibility in medical schools and during nurse training around what SCD truly is or how it impacts patients, and it has raised critical questions including “If people know about cystic fibrosis, why don’t they know about sickle cell disease?”

Dr Wale Ateyobi, Consultant Haematologist at Oxford University Hospitals and Honorary Senior Clinical Lecturer at University of Oxford, highlighted a stark exposure of existing health inequalities over the Covid-19 period – a virus that has disproportionately affected people of African or Afro-Caribbean background. Coupled with reports from the recent All Party Parliamentary Group on SCD and Thalassemia that 40% of patients with SCD feared going to hospital due to poor standards of care, discrimination, and lack of respect, there is a clear failure of care particularly for those in high deprivation areas, that translates to poorer health, reduced quality of life, and early, preventable death in SCD.

Critically, Dr Ateyobi states: “If the removal of health disparity is embedded in future health policy, we could avoid perpetuating the injustices of the past and move towards equitable healthcare for all those with SCD in the future.”

While recent inquiries have prompted promising new initiatives within the NHS to begin to address the historic challenges faced by patients with SCD, there is still a clear need for more immediate support through both the effective use of existing technologies and new ways of working. Whereas clinicians currently lack the day-to-day insights needed to inform the best care for their patients, advancements in wearable technology and digital, remote monitoring offers an incredible opportunity for improving disease understanding and tackling disparities in the standards of, and access to, care for patients with SCD.

Indeed, with this form of monitoring, clinicians will increasingly be able to see where patients have struggled and experienced pain crises that would previously have been missed, tailoring patient care to meet their true needs. Furthermore, patients are empowered with new information and the supporting infrastructure to take control of their care – something particularly important in a patient group that has for so long felt like they weren’t.

Despite the challenges, there is hope through an engaged patient community and the clinicians, researchers, and organisations that strive to support them, that change may yet be on the horizon. As Dr Lugthart, Consultant Haematologist at University Hospitals of Bristol NHS Trust, states:

“I’m hopeful that all these new things will help, that we will prove history wrong, and that we are actually making a change.”